Ana Paulina Alba Trenado

December 12,2024

THE STORY WHEN DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA (USA) MIGRATED TO SAN PABLITO (MEX)

Para la comunidad de San Pablito, con todo mi cariño y admiración por la resiliencia, el valor de enfrentar la adversidad generación tras generación.

A las mujeres otomíes, cuyo trabajo de crianza y sostenimiento de sus tradiciones y lengua otomí, por años no ha sido reconocido y valorado. Porque con su migración a Estados Unidos demostraron que como mujeres indígenas no sólo nacimos para cocinar, criar, hacer chaquira, ir a tortear y hacer hijos. Mi más profunda admiración por perder el miedo a cruzar la frontera. El coraje de ver a sus exparejas rehaciendo sus vidas y familias en EU, mientras que ustedes recién migraban para suplir el sostén de sus hijos y demás familia en sus comunidades, además de sostener sus propias necesidades en un nuevo contexto.

No romantizo la injusticia estructural y sistémica hacia este pueblo, ni el machismo que impulsó a una migración masiva de mujeres. Pero quiero expresar mi sentir a personas cuyos ejemplos de vida me han llenado de mucho valor como mujer.

GRACIAS POR SU VALENTÍA Y CORAJE.

-KAMATIKI- OJA TI JAPAÍ

“A migração nos bate à porta

Migration knocks on our door

As contradições nos envolvem

Contradictions surround us

As carências nos encaram

Needs face us

Como se batessem na nossa cara a toda hora.

As if they were hitting us in the face all the time.

Mas a consciência se levanta a cada murro

But our conscience rises with every punch

E nos tornamos seco como o agreste

And we become as dry as the wilderness

Mas não perdemos o amor.

But we haven’t lost our love.

– ELIANE POTIGUARA (“Identidade Indígena”)

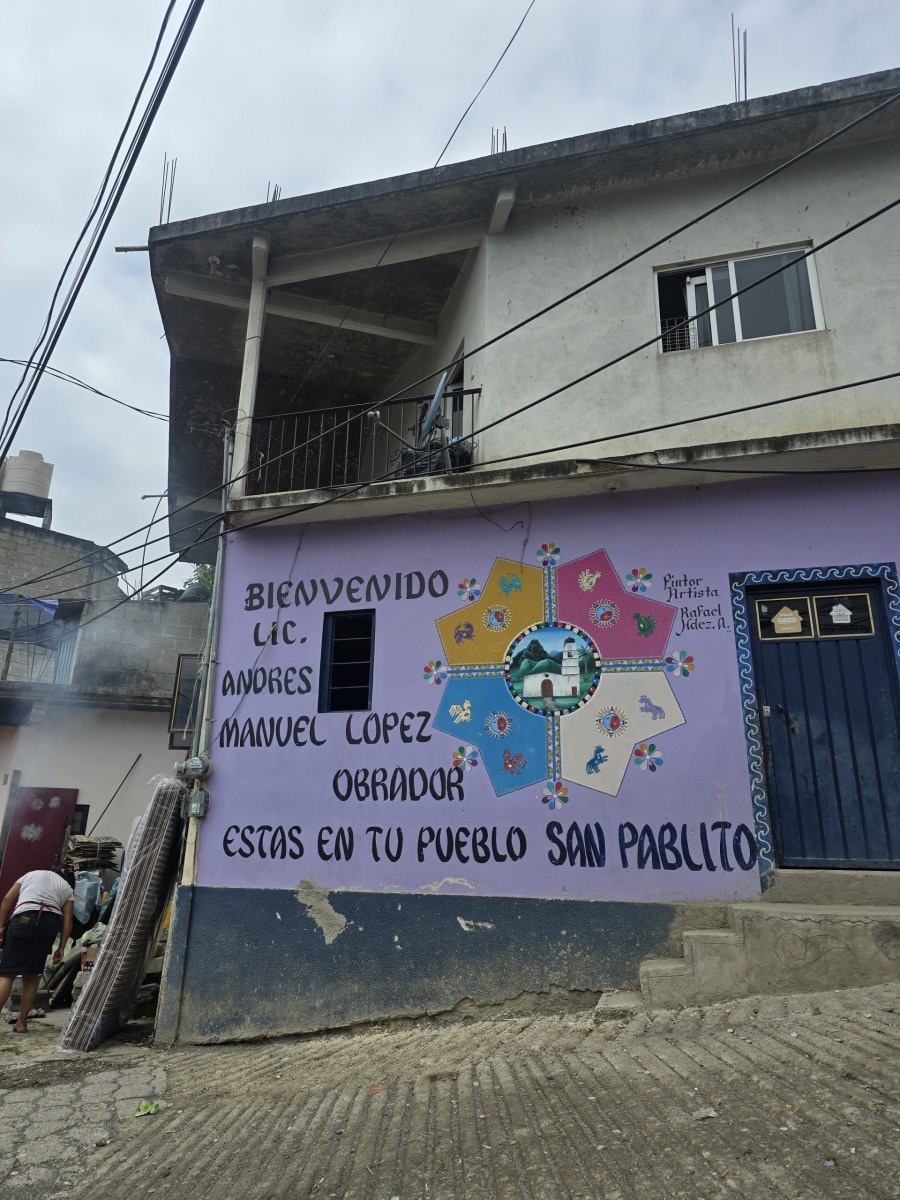

Even in the entrance of San Pablito says “Welcome ANDRES MANUEL LOPEZ OBRADOR”, the name of the last president of Mexico, It should say: “WELCOME NORTH CAROLINA TO YOUR VILLAGE, SAN PABLITO”.

This indigenous community is located in the north of Puebla, Mexico, in the municipality of Pahuatlan.

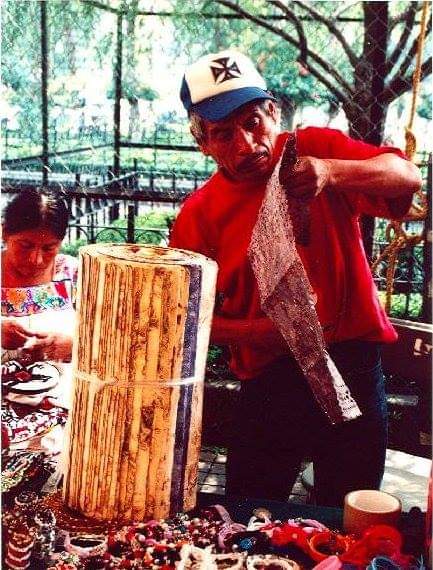

San Pablito is home of the otomi ñahñu ethnic group and it´s been considered as the amate paper home, a traditional handmade paper elaborted with the bark of the jonote tree.

The elaboration of amate paper dates back to pre-Hispanic times and contained figures of people, animals and elements of nature, such as the sun. The use of this handmade paper was considered sacred and its use was for ceremonies. According to testimonies of community elders, amate paper continued to be used for healing purposes before the arrival of western medicine, combining the use of amate paper and medicinal plants in healing practices/ rituals.

The boom in the production for sale and promotion of Amate paper outside the community occurred in the 1990’s after the decline of agriculture in the countryside by the Otomi people. This change in economic activity was supported by anthropological research during the 20th century. The anthropological work promoted the influence of a national identity that gave an important weight to indigenous elements from a folklorization and exaltation of an indigenous past, thus alluding to “valuing our roots”. This discourse encouraged the production and consumption of handmade products by indigenous communities with a pejorative value than Western art, that was the main reason to call them “handicrafts”. This period of national identity formation is known as Mexican indigenism.

“Indigenism is presented as a historical process in consciousness, in which the indigenous is understood and judged (“revealed”) by the non-indigenous (“the revealing instance”). “The revealing instance” of the indigenous is constituted by specific classes and social groups (institutions) that try to use it to their benefit.” Luis Villoro (1987)

San Pablito, like most of the indigenous communities, subsisted on agricultural production until before the decline of the Mexican countryside after the signing of the Free Trade Agreement in 1994. After the signing of NAFTA, the economy was transformed into an import substitution economy, which was also a boost to the transformation of the economic livelihood of the Otomi people in San Pablito. This community was a producer of peanuts, corn, beans, cilantro, parsley, different fruits and coffee. The Instituto Méxicano del Café (INMECAFE) began subsidizing coffee production as a development tactic from 1959-1989, and San Pablito farmers shifted from produce to coffee farming. As a result, some residents remembered leaving to work as couriers in Mexico City, where they could earn more than they did in agriculture.1

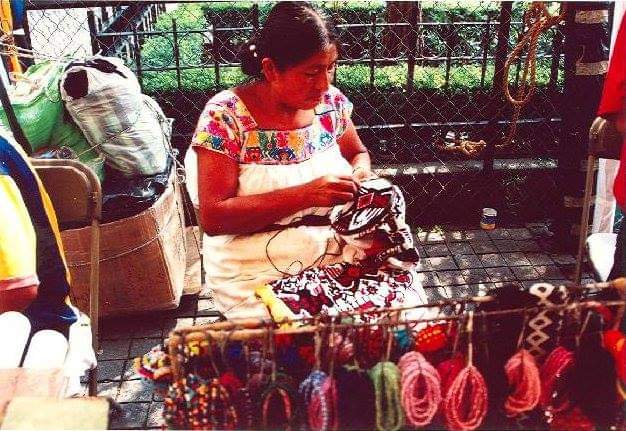

After declining agricultural production in San Pablito, the Otomi community, searching for a better income to sustain their families, began to go primarily to Mexico City and Puebla City, searching for spaces to sell and market both amate paper and chaquira jewelry. Establishing themselves near points where there was a greater flow of tourists. In Mexico City they initially occupied places such as the capital’s Zócalo, Garibaldi and, finally, they settled down to form a resident community in Coyoacán, south of Mexico City.

From the late 1980s until 2000, the production and sale of amate paper and, to a lesser extent, the production and sale of chaquira jewelry were the main economic activities that sustained the economy of San Pablito.

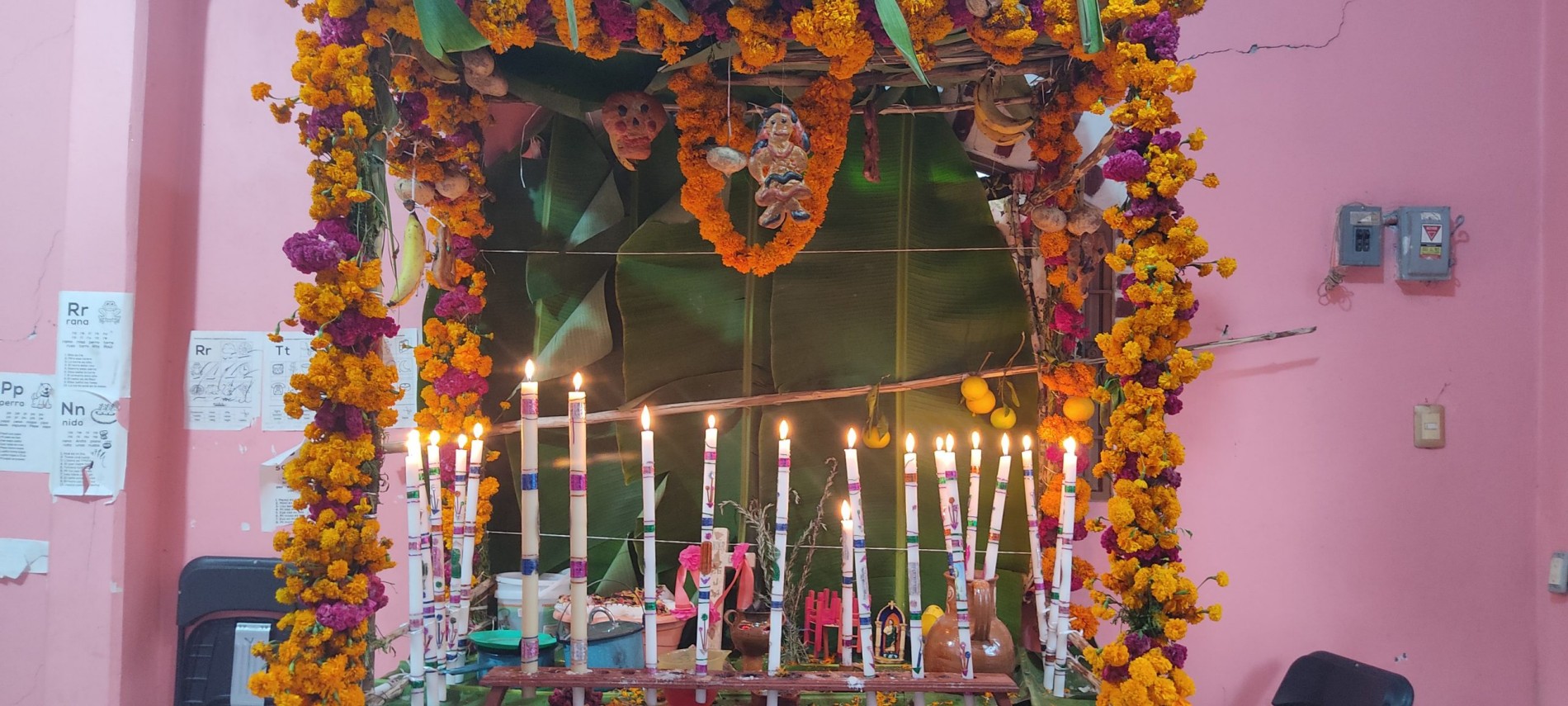

The villagers themselves bought from their own “paisanos” (countrymen), fostering a slow but steady flow of couples leaving their community to sell, with the possibility of being able to return to their community at any time due to the proximity and increased sales of their products. The return to their community took place primarily during patron saint festivities (related with the Catholic festivities), family parties, the purchase of more costume jewelry and amate paper, but especially, Otomi families returned to commemorate their deceased in November on the so-called “Día de los muertos” (All Souls´ Day)

In 2010, I visited the town of San Pablito Pahuatlan for the first time, after four and a half hour from Mexico City, from the entrance of the town you could hear from every house a standardized sound “noc, noc noc, noc, noc, noc…” It was as if all the time someone was knocking on the door, without receiving any answer.

“In the past, many families were dedicated to making amate paper, rather than chaquira. Then we saw that it wasn’t selling as much and we made more chaquira. Women and men were dedicated to making chaquira, in fact, more women than men; and other otomies went out to sell it.” Juan Santos Rojas (otomí de San Pablito)

MIGRATION PROCESS TO THE UNITED STATES

Migrations are historical processes that are not exclusive to the 21st century. Each migration process is full of very particular nuances depending on the areas and reasons that cause the movement of people and communities.

Different factors within the national and international development propitiated the necessary conditions for the Otomi people to be pushed to different migratory processes.

In San Pablito, the first large migration wave was national. The internal migration to the country that gradually expelled Otomi families from their community to different cities within Mexico.

However, in this paper, my purpose is to focus on the migration process of the Otomi people to the United States, which has also comprised different stages and key moments.

It is worth mentioning that the migratory route of the town of San Pablito was inaugurated and follows in the footsteps of the Otomi town of San Nicolas, which is located in the high part of the mountain with which San Pablito borders.

According to Mexican anthropologist Daniela Hubert, the first waves of Otomí migration from San Nicolás went mainly to orange plantations in Florida, dairies in Texas and fertilizer factories in Virginia2.

“Migrating was for men going to work in the United States.” – Anonymous (Otomí woman, 27 years old)

According to testimonies from San Pablito, the main reason for migration to the U.S. was the search for better economic conditions. Following the migratory route and relationships established by people from San Nicolas mainly with Christian groups in the neighboring country, job opportunities for the people of San Pablito grew along with the interest of U.S. Christian groups in their evangelistic mission to indigenous communities in Mexico.

Migration to the U.S. began among the Otomí of Sierra Alta in the mid-20th century as an economic option, gaining significance in the 1960s, particularly in San Nicolás, Tenango de Doria. The presence of Pentecostal Church leaders and linguists from the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL) during this time, including Don Richard, a Pentecostal pastor, was crucial in this development, especially regarding the Otomi language.

Among the families of San Nicolás and San Pablito, collective oral history indicates that some of the first emigrants to the United States did so precisely with the support of those Pentecostal priests who settled in the Sierra. Libertad, MORA MARTÍNEZ3

Although the predominant religion in San Pablito has been the Catholic religion, the impact that Protestantism has had within the community has had a strong and sustained propagation in the town.

For the most part, the affirmation of this religious belief has been strengthened by the relationship with the development of job opportunities and personal and economic development.

Within the Protestant religion in San Pablito and as part of the “evangelistic” rhetoric that involves bringing more converts to Christianity, the validation of authority and religious effervescence has brought a deepening of the relationship with the United States. From an evangelization supported by evangelical Pentecostal churches, mostly American, a relationship of support for religious expansionism has been nurtured, generating new ways of life on the part of the Otomí population, adopting elements of North American culture.These relationships today transcend the relationships established by the people of San Nicolás with Pentecostal evangelical churches. However, it is a fact that continues to determine the constant invitation for North Carolina to migrate to San Pablito to the extent that North American Pentecostal Christianity does not dialogue with indigenous spirituality, so that many cultural elements have been rejected by the new converts, thus adopting ways of life more in line with a North American Christian reality.

The second wave, which is located in the 1990s, is characterized by a massive displacement to North and South Carolina, Virginia and California, where male migrants were mainly employed in construction and carpentry.4

According to testimonies from San Pablito, the main reason for migration to the U.S. was the search for better economic conditions. This search followed the migratory route and relationships established by people from San Nicolás, mainly with Christian groups in the neighboring country. Job opportunities for the people of San Pablito grew along with the interest of U.S. Christian groups in their evangelistic mission to the indigenous communities in Mexico.

Es que aquí hay mucha gente le gusta ir a Estados Unidos, muchos ya se fueron. Todo lo que se ve ya es de Estados Unidos. Aquí la familia de junto que me ayudaba ya se fue, se fueron todos. Son 7 y allá están, migró todo el pueblo. – Artesano Juan Santos Rojas, otomi de San Pablito.

There are many people here who like to go to the United States, many have already left. Everything you see is already from the United States. Here, the family that used to live next to us and that used to help me has already left, they all left. There are 7 of them and they are there (in the US), the whole town has migrated. Artisan Juan Santos Rojas, otomi from San Pablito.

The first two waves of migration to the United States were characterized by being primarily led by men. The male figure was conceived as the economic provider and the woman as the economic provider and caregiver.

“Antes sólo se iban los hombres a Estados Unidos, está difícil irse para “el otro lado” – Aidé Hernández, mujer otomí de San Pablito.

“In the past, migration was for men going to work in the United States, it’s hard going to the US .”

My main contribution is based on the description of the third migratory wave from the bases that were built with the migratory waves that preceded it. But above all, I offer a feminist perspective on the analysis of the previous migratory waves.

“Looking at history from a feminine point of view implies a redefinition of the accepted historical categories that make visible the hidden structures of domination and exploitation". Silvia Federici.5

The third wave of migration of the Otomí community occurred after the COVID 19 Pandemic.

Economic conditions worsened when the pandemic forced Otomí families who had already left their communities and who were dedicated to selling mostly chaquira jewelry in the streets, to leave their sources of income.

Selling in the streets was prohibited and there were even threats of withholding their merchandise if they were seen selling in the streets due to the severity of the spread of the pandemic.

Many of these families, after the lack of economic resources to sustain themselves, to pay rent and food, decided to return to their communities. This return was the evidence of territorial dispossession as a result of migration process. Most of the families no longer had a place to stay, the families that had already formed and were children and grandchildren of the first wave of migration to Mexico City, no longer had the tools to survive for longer in a rural area, in their Village. Other families tried to stay in Mexico City in the hope that everything would soon return to normal, exchanging their chaquira products for food, walking long hours in the streets trying to sell something to support their families.

In the first six months of the pandemic, families had no incentives or support from government institutions. In addition, there was the demand from schools for children to be connected by video call to their classrooms. This was a challenge for the conditions of lack of access and information on the use of ICTs by Otomi families.

Economic conditions worsened when the pandemic forced Otomí families who had already left their communities and who were dedicated to selling mostly chaquira jewelry in the streets, to leave their sources of income.

Selling in the streets was prohibited and there were even threats of withholding their merchandise if they were seen selling in the streets due to the severity of the spread of the pandemic.

Many of these families, after the lack of economic resources to sustain themselves, to pay rent and food, decided to return to their communities. This return was the evidence of territorial dispossession as a result of migration process. Most of the families no longer had a place to stay, the families that had already formed and were children and grandchildren of the first wave of migration to Mexico City, no longer had the tools to survive for longer in a rural area, in their Village. Other families tried to stay in Mexico City in the hope that everything would soon return to normal, exchanging their chaquira

Conditions became increasingly acute. Corruption in their workplaces where they were gradually returning to, but now with fees from the government of the Mayor’s Office of Coyoacan, in Mexico City for allowing families to return to their workplaces, streets, open spaces where national and foreign tourists walked.

Another important factor is that since the second wave of migration, the sources of income within the cities, mainly Mexico City, had expanded, opening up work spaces for women and adolescents in restaurants in the vicinity of where the rest of their families sold their products.

“Yo iba a dejar a mi hija a la escuela, después me iba de lavaloza a Coyoacán (a un restaurante). Ya salía como a las 12 o 1 de la mañana y llegaba a revisar la tarea a “la Andrea” (una de sus hijas), estaba en un ahí en Coyoacán para estar cerca de mis hijos por lo menos, por si pasaba algo ahí estaba cerca.” Rocío Valerio. Otomí ñahñu

I would drop my daughter off at school, then I would go to Coyoacán (to a restaurant) to wash dishes. I would leave around 12 or 1 am and I would go to “la Andrea” (her daughter) to check my homework, I was in a place in Coyoacan to be close to my children at least, in case something happened there, I was close to them.

During the pandemic, many of the restaurants where Otomíes worked closed because they could not afford to pay the high rents in the tourist areas where they were located. Within these places, the exploitative working conditions of women and young people who had no health insurance or benefits, were dismissed or suspended until further notice, most without pay.

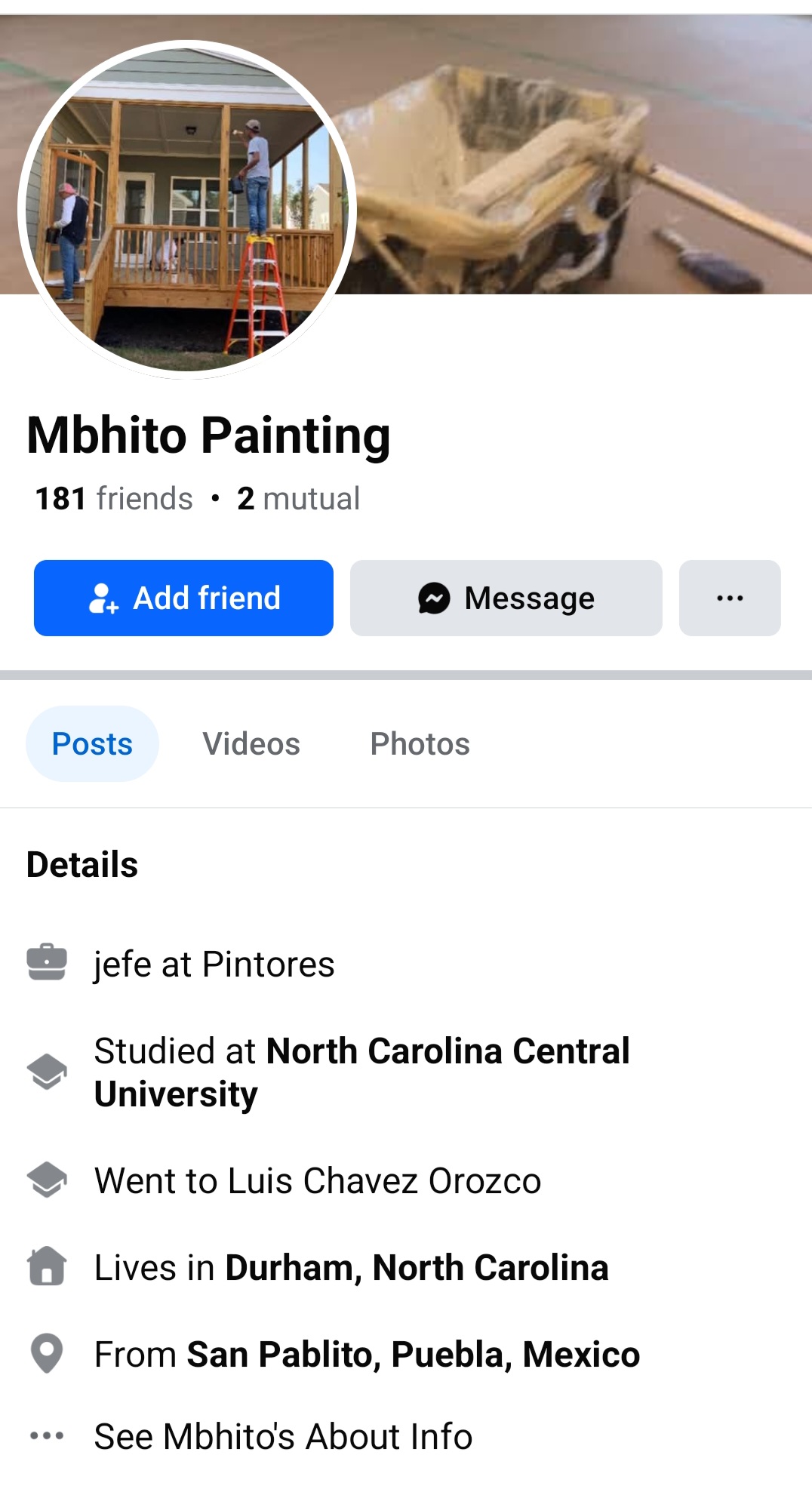

By the third wave, many men had emigrated to the United States and many of them, already established in Durham, North Carolina, had achieved the stability to open their own painting and construction businesses. Some others had managed to obtain positions within American-owned companies, which allowed them to become managers and hire others.

Mbhito is the name of San Pablito Village in otomi language.

Within the third wave of migration to the United States, women took the leading role.

Looking at history from a feminine point of view implies a redefinition of the accepted historical categories, making visible the hidden structures of domination and exploitation. Silvia Federici.

The women who had been left waiting for their migrant husbands and in charge of raising the children were also the ones who for a long time maintained the reproduction of the traditions and the reproduction of the Otomí language in San Pablito. Now they have made the decision to migrate.

“Los hombres dejaron de mandar dinero. Dijeron que se quedaron sin trabajo, pero luego me enteré que ya tenía otra familia allá. Le dije que aunque sea mandara dinero para su hijo.” Anónimo (mujer otomí de San Pablito, 27 años)

“The men stopped sending money. They said they were out of work, but then I found out he already had another family there. I told him to at least send money for your son.” Anonymous (Otomi woman from San Pablito, 27 years old).

The degraded image of women subjected to an everyday life that did not recognize the value of child rearing and their role in the conservation and reproduction of language and traditions, became a factor for women to follow the practices that men had initiated in search of economic resources to support the family.

Within the first two migratory waves, the development of a new social division of labor deepened by the conditions brought about by the Pandemic in 2019 took shape. As mentioned by Feminist theorist Silvia Federici regarding the development of a new sexual division of labor that subjects female labor and the reproductive function of women to the reproduction of the labor force, which as a result brought about the construction of a new patriarchal order based on the exclusion of women from wage labor and their subordination to men.6

The lack of recognition and the abandonment by Otomi men of the vision of the purpose for which they had migrated, which had been built on their role as providers in the community, drove the massive migration of women to North Carolina. The need for women’s labor force in child rearing, care giving, food production, and meeting the needs that the construction of their “role as women” now required was in the United States.

“Hay chavas que se vienen porque ya conocen a sus parejas, y ellos las traen y viven aquí. Y las mujeres ya se dedican a ser amas de casa. De los otomíes, si hay hombres que buscan a una ama de casa porque los hombres a veces trabajan más de lo que trabaja una mujer y quieres llegar a su casa y encontrar comida. Así que las mujeres vienen para juntarse acá.” Anónimo. Mujer otomí migrante en Durham.

“There are girls who come because they already know their partners, and they bring them and live here. And the women are already dedicated to being housewives. From the Otomíes (located in NC), there are men who look for a housewife because the men sometimes work more than a woman works, and they want to get back to their house after work and find food. So the women come to find a men here.” Anonymous, Otomi migrant woman in Durham.

The capitalist systemic necessity generated the need for the female labor force in a new geography and with different nuances. For example, according to the testimony of Otomi migrant women in Durham, the hours of work are less paid than those of men. Some mention that it is because “women can’t carry much, but we also work. If there is a lot of work we get eight hours a day.”

According to the 2020 population and housing census7, there were 3,386 people living in San Pablito, of which 1,151 are under 14 years old, 930 people between 15 and 29 years old, 1,003 people between 30 and 59 years old, and 299 people are over 60 years old. If we consider that the migrant range was between 15 and 40 years of age, we are talking about a migratory exodus of more than 1,000 people in a period of no more than 5 years.

The migration of women since 2019 has constituted a new paradigm in San Pablito Village for new generations whose both parents are “del otro lado” (in the US).

Today child migration is blunting the next wave of migration after having already achieved some infant inflows through political asylum.

New challenges are being faced but not all migration is unidirectional.

THE RETURN… ONLY CAROLINA RETURNS.

Remittances from migrants today are what sustain the few people who remain in San Pablito, they are also the ones who come to buy the jewelry of the few women who remain in the village.

But not everything has been one way, there have also been returns.

Of the first and second wave of migrants, there are already generations that have the necessary documentation to go and return to North Carolina, but she herself, “Carolina”, has been in charge of settling in San Pablito.

The greatest demonstration of North Carolina’s migration to San Pablito has been the architectural transformation of wood with grass or sheet metal roofs small houses

… into architectural replicas of a North American culture.

Constructions were paid for with the unpaid wages of women’s labor in both geographies. Mothers of families who remained in the upbringing while a palace was built for them that is now empty because they also migrated. But there is also the salary of the old women, caretakers of those palaces, but who do not dare to inhabit them and who remain in some of their little wooden houses, but who daily and religiously turn on the lights “so that other people do not get in”, guardians who watch over the builders while they change the roof tiles that are falling off due to humidity, old women who bear witness to the enlargement of the houses and the dreams of sons, daughters, grandchildren and great-grandchildren who have gone to bring Carolina to come and live in San Pablito.

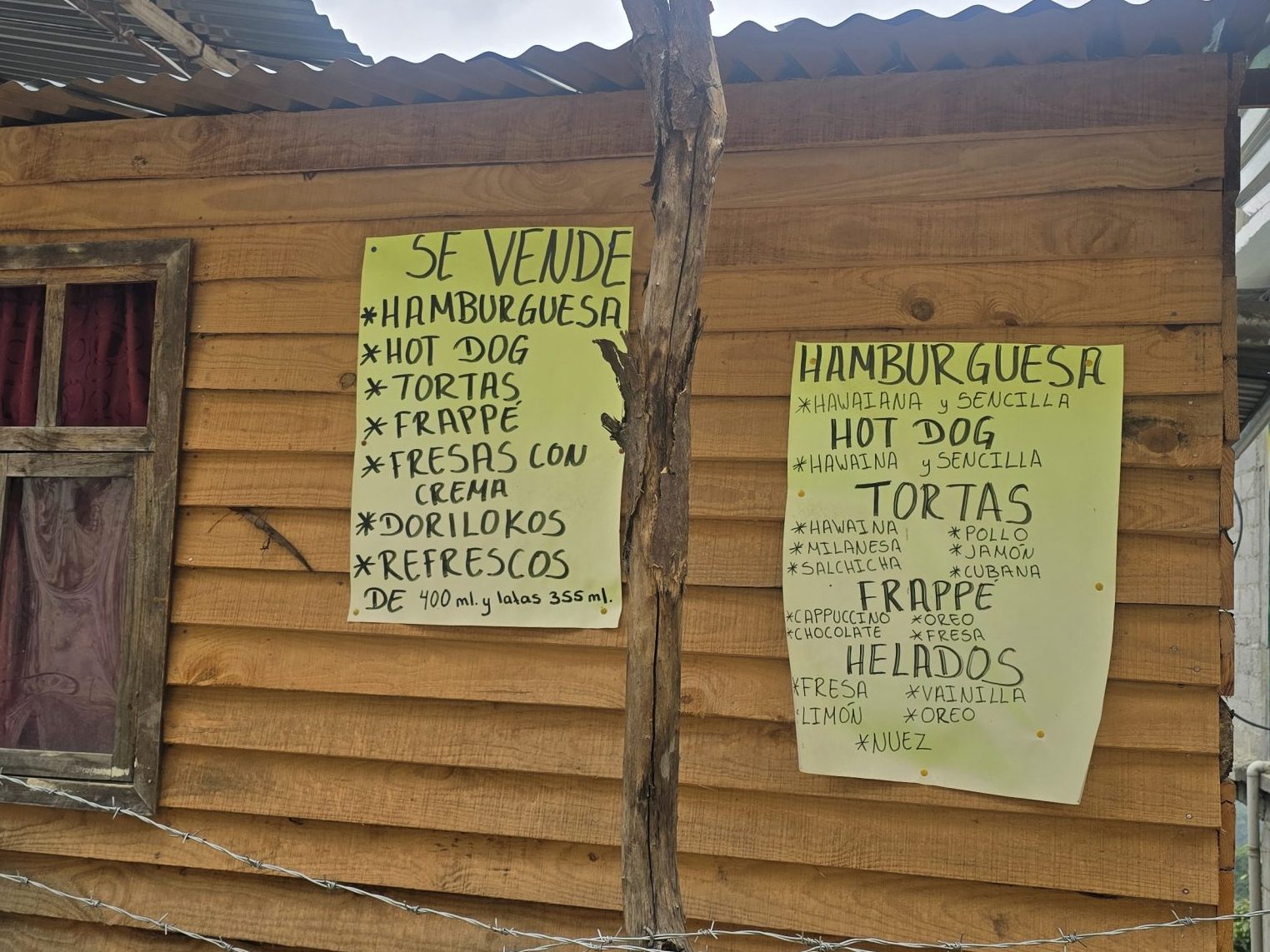

However, North Carolina carried suitcases, where they also moved their clothes and food.

Instead of molotes, tortillas, salsa, and the local avocado called “Pahua”.

Now a days, North Carolina is pushing to share it´s own food in San Pablito

One of the immigrants who returned for a few months to San Pablito from Durham, NC, opened a small place to sell hot dogs, hamburgers, soft drinks and strawberries and cream in a place that about 5 years ago sold traditional quesadillas and tacos. This place is susteined by his wife, who still living in San Pablito.

By the way, North Carolina does not have to pay the “Coyote” to cross the border. NC crossed legally into San Pablito.

“Nosotros pagamos hasta 12,000 Dls que nos prestan nuestros paisanos. Ellos les pagan al coyote cuando nosotros llegamos Durham y luego tenemos que trabajar para pagarles y también para juntar para mandarle dinero a mi familia, ya vez que yo dejé a mis tres hijos allá.” R.V. (25-year-old woman, from San Pablito in Durham).

We pay up to 12,000 that we borrow from our fellow countrymen. They pay the “Coyote” when we arrive in Durham and then we have to work to pay them back and also to raise money to send money to my family, since I left my three children there.)

When NC arrives in San Pablito, where does she sleep?

NC stays in the uninhabited homes of every Sanpabliteño migrant who is still in Durham with the dream of returning to his hometown.

Those ostentatious houses for a town that not more than twelve years ago had a mountain on the highway that had to be sacrificed by the Cement Company, to extract construction materials required for the development of cities like the one San Pablito is becoming today.

- Bethany Alhenius. (Re)Constructing Home, Beyond Mbithe: Rural-Urban and Transnational Migration in the South Huasteca Otomi. Prepared for delivery at the LASA 2020 Virtual Congress of the Latin American Studies Association, May 13-16 2020 ↩︎

- Libertad Mora Martinez. From the Sierra to the Coast. Otomi Transnational Migration:The Hñähñü of the Huasteca Poblana ↩︎

- Ibidem – Tesis ↩︎

- Huber, D. (2011). Flujos y circuitos. Procesos migratorios y relaciones de género en dos comunidades otomíes tenanguenses. El caso de San Nicolás y San Pablo el Grande. Estudios De Cultura Otopame, 7(1). Recuperado a partir de https://www.revistas.unam.mx/index.php/eco/article/view/24078 ↩︎

- Silvia Federici. Calibán y la bruja. Mujeres, cuerpo y acumulación originaria. Ed. Traficantes de Sueños, 2010. ↩︎

- Ibidem. ↩︎

- Population and housing census 2020, Mexico. Online consulting 12/12/24.

https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/areasgeograficas/?ag=211090014#collapse-Resumen ↩︎